Blog

The wild legacy of Douglas Tompkins

Today is a day of celebration in Chilean Patagonia. The Pumalín and Patagonia national parks are this morning officially being passed into the hands on CONAF (the national forest of Chile) as part of the Route of the Parks conservation project.

It's also a day of reflection and thanks because Douglas Tompkins, the man who started this journey three decades ago, is sadly not here to join us in the celebrations. This is therefore a sincere thank you for the wild legacy of Douglas Tompkins and the tireless work of his partner Kristine Tompkins to realise their shared vision.

From the board room to wilds of Patagonia

Douglas was the founder of the North Face and Espirit clothing brands, a mountain climber of note who happened to be a brilliant businessman. But it's what he did with his money that is his legacy. In the late eighties he sold his business interests and moved to Chile.

"The fashion business is not the business to be in if you’re trying to contribute to diminishing the impact on nature."

For the next 25 years or so Douglas and his wife Kristine brought up strategically important, environmentally vulnerable tracts of land in Chile and Argentina, primarily Patagonia, to protect them. The vast majority of this was purchased from absentee landowners or those struggling to sustain their unprofitable farms. The habitats were being destroyed by overgrazing or were under threat from development. Estancia fences were blocking traditional wildlife passages.

I remember living in Santiago de Chile in the early 1990s when the country's press, people and parliament were up in arms about Tompkins' Parque Pumalín project. They had purchased a stretch of precipitous forested mountains around the town of Chaitén.

The plan was to protect the ancient Andean Larch (Alerce) forests. These trees are amongst the oldest, and slowest growing, in the world. They routinely grow for over a thousand years and sometimes manage three or more. Unfortunately for the Alerce, they produce wood so valuable that people go to almost any lengths to chop them down.

“If anything can save the world, I’d put my money on beauty.”

He took a huge area of Alerce forest and kept it safe. Not only did Douglas promise to protect it, he also said that the land would be prepared for donation to the Chilean state as a National Park. Nobody believed him.

Pumalín is located at the narrowest point of Chile and runs from the Argentine border to the fjords of Chile's Pacific archipelago. Argentina's great strategic aim has always been to get a Pacific port - it's the source of constant tension between the two countries.

A foreign entity coming in and buying a cross section of the country sent Chile's media into a flat spin. Pumalín was very widely believed to be some sort of Argentine sponsored Trojan horse. Very, very few believed the official Tompkins story - that it would be given to the Chilean people.

“We were famously called the couple that cut Chile in half. They thought Pumalín was being developed to create a new Jewish state, or as a new nuclear waste dump for the United States.”

Tompkins pointed out that the land was completely inaccessible - sheer mountain side that couldn't possibly be crossed by man or beast. Eventually, that accusation faded only to be replaced with the rumour that they were about to start uranium mining.

Another, more outlandish, was that Tompkins would be setting up a Zionist foothold. Nobody quite explained why a lapsed Anglican would be doing this, nor why Jewish settlers would be flocking to this spectacularly wet corner of South America. Some said that they were building a UFO car park.

I remember clearly that the most controversial opinion to express in Chile at the time was that maybe, just maybe, he was telling the truth.

Not only was Pumalín donated to the Chilean state as national park but the Tompkins work set off a new fashion for grand environmental philanthropy in Chile. Rich individuals, corporations, even the Chilean military got in on the act and started to protect and donate lands to the state.

A wild legacy

For Tompkins too, Pumalín was just the start. Their passion for the environment, for Patagonia in particular, meant that their fortune, energy and time was to be dedicated to the process of purchasing vast areas of ecologically significant lands across the region to make sure that they weren't destroyed.

“I tell myself to hurry up, that I have to do everything before death catches up with me.”

The Tompkins household in Parque Patagonia

There are millions of hectares of Chile and Argentina which are protected for good, because of this man's vision. It's not to pretend that Douglas Tompkins wasn't a controversial figure, but there's no doubt that he was a visionary, nor that he has left a legacy of global significance.

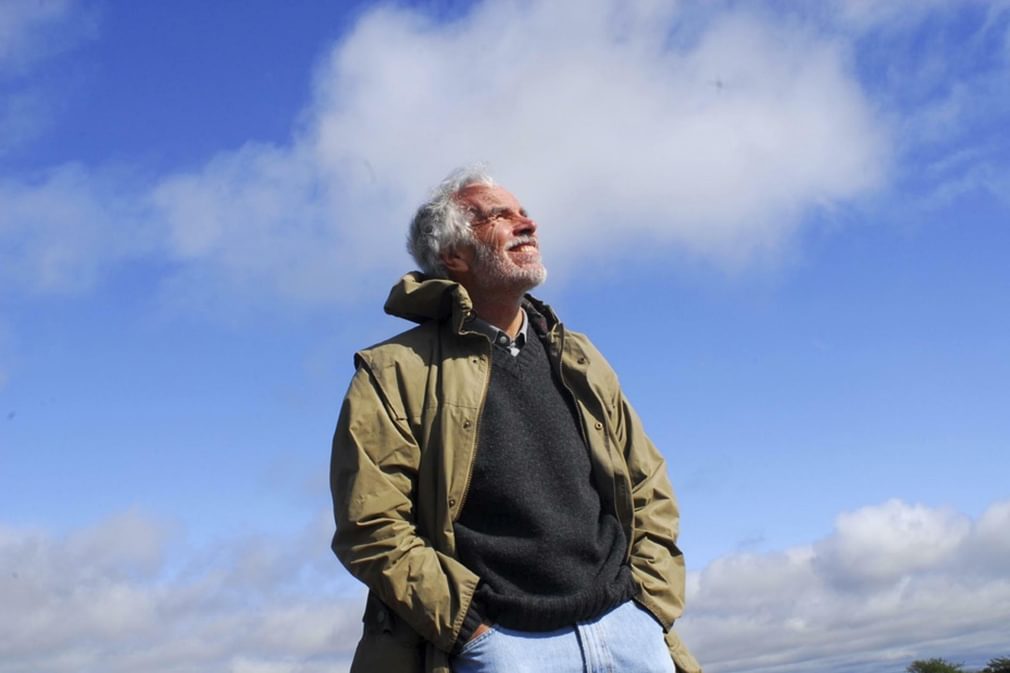

I met Douglas a couple of times down in Southern Chile when I was at his newest grand project: the future Parque Patagonia. He was there with people from the Argentine parks authority discussing ways in which they could create cross-border infrastructure. I was coming back from a hike through the Parque. Douglas' energy was palpable. He wanted to know what I thought of the park, how I'd found the trails, what I'd seen that day - he loved to hear people loving the landscape.

Douglas Tompkins had been exploring and enjoying Patagonia for the best part of 50 years and I think he just wanted to share. Patagonia does that to a person. It's exactly what happened to me when I first went there in the 1990s.

In December 2015, Tompkins died suddenly while kayaking on Lago General Carrera - adventuring in the heart of remote Patagonia on the most beautiful lake imaginable. His legacy has been assured thanks to the unceasing determination, passion and force of character of Kristine. For my part, I'd like to again just say thank you to both of them for doing so much to protect my beloved Patagonia.

The Route of the Parks

Together, the two new national parks form part of the greatest private land donation in history and will offically become part of the world's biggest ever conservation project. The Route of the Parks protects 11.5 million hectares of land, from Puerto Montt in the Lake District all the way down 2,800km of road and sea to Cape Horn. It is one of the world's great road trips, topped off perhaps with one of its great expedition cruises.

We are extremely proud to be the first non-Chilean tour operator associated with the project, allowing us to share the places in Patagonia that have most moved us, with more people. We'd love to share it with you, so that you too can be moved by places like Patagonia National Park and Pumalín.

Actually, it's about time I started using the Pumalín's full name: Parque Nacional Pumalín Douglas Tompkins.

The Pothole is Pura Aventura's popular monthly email. We share what we love, what interests us and what we find challenging. And we don't Photoshop out the bits everyone else does. We like to think our considered opinions provide food for thought, and will sometimes put a smile on your face. They've even been known to make people cry. You can click here to subscribe and, naturally, unsubscribe at any time.

The Pothole is Pura Aventura's popular monthly email. We share what we love, what interests us and what we find challenging. And we don't Photoshop out the bits everyone else does. We like to think our considered opinions provide food for thought, and will sometimes put a smile on your face. They've even been known to make people cry. You can click here to subscribe and, naturally, unsubscribe at any time.